The Renaming of Camp 4.

For half a century Camp 4 has been the climbers’ base camp in Yosemite. Yet for most of that time, the National Park Services insisted in calling it “Sunnyside.” That difference came to symbolize the conflicts between climbers, the NPS, and the Curry Company. In 1999, the NPS acknowledged the end of decades of feuding by announcing the site’s name would once again be Camp 4. Now, an exchange of e mails between Gary Colliver of the NPS and Armando Menocal, Founder of the Access Fund, reveals how the historic change came about.

The Untold Story of the Renaming of Camp 4

By Armando Menocal

At the September, 1999, Celebration at Camp 4, the National Park Service announced that Camp 4 would be officially re-named “Camp 4”. Of course, its always been Camp 4 to climbers, but that name for the climber’s camp had stuck in the Park Service’s craw for half a century.

With the end of the first “Golden Era” of Yosemite climbing about 1970, and attempting to attract other than climbers, the Park redesignated Camp 4 as “Sunnyside”, even though all of the other campgrounds in the Valley retained their historic numerical designations.

Camp 4’s place as one of the centers of American and even international climbing culture has been documented in legend and literature. In 1969, Doug Robinson, wrote in Mountain that, “Camp 4 is the physical and spiritual home of the Yosemite climbers.” In a description that rings true almost 40 years later, Robinson said of Camp 4:

“In spite of the spectacular setting, it has become the most trampled and dusty, probably the noisiest, and certainly the least habitable of all Yosemite’s campgrounds. . . . Yet the Yosemite climber will stay nowhere else.”

The Park and Curry Company, Yosemite’s sole concessionaire, tried repeatedly to get rid of Camp 4. Of course, at first it was climbers that they wanted to constrain or remove by closing their refuge. Eventually, even Camp 4 became an anachronism to the authorities. Camp 4 remained small and cheap as Yosemite developed large campground suitable for behemoth Winabagos; a walk-in campground with irregular, often crowded, well lived-in sites was impossible to police or to cruise from a patrol car.

Preserving Camp 4 may have been one of the earliest climbing access causes, first championed by Raffi Bedayn, a Yosemite climber in the 1930s and 1940s and manufacturer of one of the first aluminum carabiners. For the next 30 years, Raffi took up the unpopular cause of defending Valley climbers. If they were climbers, it didn’t matter to Raffi that the Park Service or Curry Company saw them as low-life, scavengers, and petty thieves, which sometimes, some of them were. Whenever animosities were high between climbers and rangers, Raffi would show up at the Valley to ease tensions with his unassuming, irrepressible diplomacy. Raffi’s years of personal, hands-on service to the climbing community were recognized, and he was the first recipient of the American Alpine Club’s Angelo Heilprin Citation. After Raffi’s death, grateful climbers placed a memorial for Raffi at the base of Midnight Lighting on Columbia Boulder.

On the surface, the names Camp 4 or Sunnyside may not seem very important, but in fact the renaming represented a huge shift of official attitude. Refusing to acknowledge the climbers’ name for the most famous campsite in the climbing world was emblematic of the demeaning status of climbers in the Valley.

It is hard today to recall that at one time, climbers were regularly run from Yosemite Lodge (curiously, in the 80s Lodge employees were instructed not to give apparent climbers coffee refills), swept from Camp 4 and its parking lot (one Yosemite Superintendent told a group of climbers that their interests were as important to him “as a dumptruck load of dirt”), and its closure was threatened throughout the 70s, 80s, and 90s.

Even in the massive Climbing Management Plan that the Park, climbers, and other conservationists developed in the 1990s, the NPS would not yield on the epithet, Sunnyside. The name had become the symbol of contention.

The struggle to save Camp 4 from “re-development” after the 1997 floods forced the Park Service to acknowledge and respect the role and history of climbers in the Valley. The final acknowledgement that the decades of feuding were over was when for the first time the Park Service announced that the site would thereafter be officially called Camp 4. The change was announcedat the September 1999 Celebration, and it brought grateful cheers from the hundreds of Valley climbers from the 60s, 70s, 80, and 90s.

The “back story” of how the change came about has never been disclosed. This is how it came about. It is revealed in the exchange of emails between Gary Colliver, a well-known Yosemite climber who had become one of the Park’s planners, and Armando Menocal, who had been a Yosemite activists since 1980 and a protégé of Raffi Bedayn, showing up everytime that Camp 4 was threaten with closure. Although often antagonists over climber issues, the two long time Valley climbers had become friends, even arguing over the climbing plan, when they climbed together.

Two weeks before the celebration, Armando wrote to Gary:

Hi there Gary.

I will not be at Camp 4 celebration this month. . . . I assume that the Park will have someone there speaking at the celebration, and I wanted to repeat (at least to you, and perhaps you'll pass along) that there's almost nothing that the NPS can do which will signal to climbers that the NPS gets the importance of Camp 4, than to rename it, "Camp 4." Think of what a great thing it would be to announce that at the celebration! The day after the announcement at the Celebration, Gary wrote back:

Armando:

Talk of renaming has been going on for several years. I think you or Paul Minault [Access Fund Regional Coordinator] may have begun the discussion during our work on the Climbing Management Plan back in the early '90's. Hal Grovert, the previous Deputy Superintendent said we should do it over a year ago. Often the way things work here is that something is talked about on and on, but an actual decision is not made, recorded, or acted upon. As it happens, your mentioning it, caused me to once again mention it to Chip, who thought it a good idea and took it to the Superintendent the next morning, and the decision was made. So, if you and I (and others) had not been persistent and not lost hope in the process, and kept gently pushing the idea forward, it may have eventually occurred, but not at this auspicious moment. In fact, it may have been waiting and watching for the right time to mention it again that did the trick.

Thanks! Best wishes,

Gary

I think Raffi is looking up at Midnight Lightning with a small smile and reminding us to be content with small victories.

END

Armando Menocal climbed in Yosemite for 25 years with first ascents in the Valley and Sierra Nevada, including the first ascent of the West Face of Mt. Watkins. Now a rock and alpine climbing guide with Exum Mountain Guides, Armando lives in Wilson, Wyoming, and is spearheading introduction of climbing and guiding in Cuba. He is the creator ofwww.CubaClimbing.com, a complete guide to Cuba for climbers and other adventure travelers. Armando has been a human rights and environmental activist and is Founder of the Access Fund, the largest organization of climbers in America.

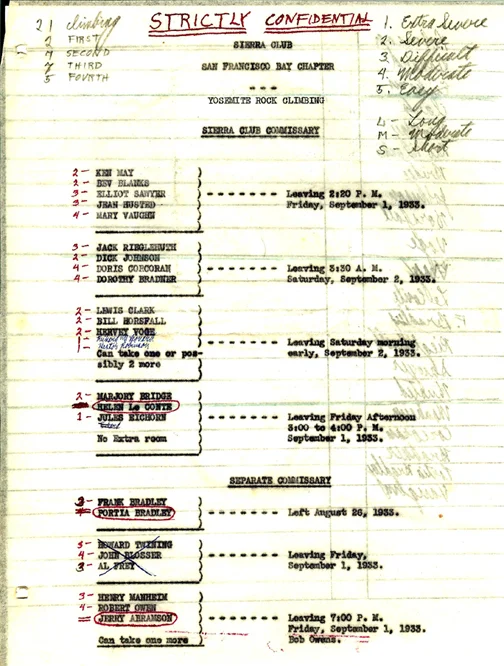

The story of the pins as told by Ronald Hahn.

These are a few remarks on the design and production of the Sierra Club Rock Climbing Section’s second climbing pin, introduced sometime around 1954.

In one of the showcases at the recent exhibition, “100 Years of Climbing in Yosemite”, at the Yosemite Museum, there was a well-seasoned hat, donated by Robin Hansen. The hat dated from at least the early 1950s, when I first saw it. The hat had two Sierra Club Rock Climbing pins attached, similar to the above.

Torcom Bedayan (Raffi’s brother) was the designer of both of the pins, but we took some liberties with the design of the second pin. I knew Torcom when I climbed with the SCRCS in the early 1950’s. (I would like to interject a note about Torcom’s artwork during World War II. Some of Pvt Torcom K. Bedayan’s paintings became part of the US Army Art Collection. I believe that I saw one of his paintings hanging in a corridor of the Pentagon in later years, but my memory may be faulty. In preparing these notes, I ran across references to his artwork in a 1942 issue of Life Magazine and in a collection of WWII Christmas Cards. At one time I owned a small paperback book of WWII military art, which included one of Torcom’s paintings.)

I do not know the history of the first climbing pin used by the SCRCS. It was manufactured by Metal Arts Co, Roch. NY. The company is apparently still in business.

I do know that there came a time, around 1953, when the SF Chapter of the SCRCS was running short of these pins and the Rock Climbing Committee decided to order new pins.

But it was not that simple. The first pin was a beautiful work of art, but the colored enamel had a tendency to chip when it came between a rock and a hard place. There were also complaints that some of the lettering was hard to read. There was even a complaint that the climber’s foot-work was suspect. (You'll note that the ledge is not filled in.)

As a young climber, at the bottom of the pecking order so to speak, I was given the task of reordering the pin. I was also given many of the comments and complaints regarding the pin. I discussed the comments with Torcom and he was extremely patient and gracious in resolving the issues with me. He came up with this design for the new pin:

When we had agreement on this design from the leading members of the Rock Climbing Committee, Torcom produced more durable artwork that could be shopped to the various vendors:

When we started getting bids from potential vendors, we also started to nail down the particular details of the artwork.

For example, people preferred a slack belay, rather than tension. Handholds and footholds were produced. Rope texture and a carabiner are portrayed. You get the point.

I cannot explain my inability to produce a more accurate background. I did take hits on that, also.

I do remember bringing these issues up with the final vendor and his patience in responding to our nit-picking. I do not recall how we came to agree on the red enamel border, other than the fact that it must have looked good with the metal artwork. As it turned out, I don’t think the red enamel aged well, and it, too, was susceptible to chipping.

I should say that I have always thought that the 2nd pin was produced by Art Metal. But I see that the first pin is labeled Metal Arts Co. Now I wonder if we did business with the original vendor, after all. I cannot remember. I also do not recall the price of the pin.

I am depositing the original artwork in the YCA archives.

--Ronald Hahn

Poughkeepsie, NY

February, 2009

Climbing the Granite Frontier, From Muir to the Masses

By MICHAEL J. YBARRA

In 1869 John Muir scrambled up a soaring granite tower named Cathedral Peak, becoming the first person to stand atop the table-sized summit, which offers a magnificent view of California's High Sierra.

The Nose on El Capitan has become a magnet for speed-climbers.

"No feature, however, of all the noble landscape as seen from here seems more wonderful than the Cathedral itself, a temple displaying Nature's best masonry and sermons in stones," Muir wrote. "This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California. . . . In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars."

Muir was Yosemite's first climbing bum -- a rara avis then, but a species that is not at all endangered today. Witness the queue to get a tent site in the park's Camp Four, where bedraggled climbers with duct tape holding their down jackets together mass early every morning hours before the ranger station opens. And those are the orderly ones, not the so-called dirtbags who sleep illegally in the bushes, ignoring the regulations and spending months at a time in the park pursuing their passion. It's not uncommon, moreover, to find climbers lined up to scale popular routes such as Cathedral Peak, although most use a rope to protect themselves from falling off the summit -- unlike Muir, who trusted all to his hands and feet and steady nerves.

El Capitan:Corbis

The ascent of Cathedral Peak was notable not just for its physical accomplishment but even more so for the mental

aspect, which in Muir's case was inescapably spiritual. The son of a harsh, itinerant preacher who viewed all fun as

frivolity, Muir transmuted his father's stern philosophy into an unreservedly generous worldview that marveled at the wonder of nature and saw God's love manifested in every petal of a flower or broken chunk of gleaming granite. To Muir climbing was not merely exercise but essentially an act of transcendence. Climbing, like love to Paul Valery, was "where self and not-self meet."

It's also a lot of fun. That's something I was reminded of again and again walking through a new exhibit that recently opened at the Yosemite Museum. Called "Granite Frontiers: A Century of Yosemite Climbing," the show traces the evolution of the sport from Muir's ascent of Cathedral Peak to the speed-climbing frenzy that has seen the record for running up the Nose on El Capitan repeatedly bested in the past year (it currently stands at 2 hours, 37 minutes and 5 seconds, although most people take three days or longer to do the route).

Jonathan Bayless/National Park Service

Left:Visitors explore the climbing exhibit at the Yosemite Museum.

The exhibit was organized by Ken Yager, who in his dirtbag youth spent two years living in a cave in the park and now runs the nonprofit Yosemite Climbing Association. The show, which is on display through Nov. 9, uses photos, artifacts and the words of participants to try to explain the exploits of climbers to those who usually see them only as dots on the sheer walls surrounding Yosemite Valley.

Although the start of mountaineering as a leisure activity is usually dated from the first ascent of Mount Blanc in 1786, no single place has been more crucial to the development of technical climbing as we know it today than Yosemite, the proving ground for much of the equipment and techniques that currently define the sport.

Muir, unlike many weekend warriors who rack up with thousands of dollars of space-age equipment, was a minimalist. A blanket, a crust of bread and a drinking cup constituted his usual kit. Muir's tin cup is on display, adorned with his signature, much like modern climbers who mark their gear (I use nail polish).

A lot of metal is on exhibit, including about 100 pounds of pitons, the minute engineering advances of which perhaps not every visitor will find fascinating. One neat feature is a section of granite spilt with cracks where visitors can practice placing nuts and caming devices -- the removable gear to which climbers clip their ropes for protection. Although judging by some of the poor placements I saw, I hope the people in front of me weren't heading up a real wall anytime soon.

But the real advances in climbing have been conceptual, mental breakthroughs of what is thought possible, rather than pure engineering triumphs.

In 1870, for example, Josiah Whitney looked at the towering blank mass of Half Dome and quailed. "Perfectly inaccessible, being probably the only one of all the prominent points about the Yosemite which never has and never will be trodden by human feet," he wrote.

"Five years later," the show dryly notes, "Half Dome was climbed."

That was George Anderson's ascent, when he drilled eyebolts up the smooth side of the monolith, standing on each successive rod to place the next and then fixing lines to the summit so that others could follow.

Anderson's use of equipment to ascend a rock face makes him the first "aid climber." "Free climbers," by contrast, use equipment only to catch a fall but do the actual climbing with their hands and feet -- and sometimes elbows and knees. These contrasting approaches were re-enacted by the two climbers who most pushed the modern boundaries of the sport in the Valley in the 1960s: Warren Harding, who made the first visionary aid climb of El Cap, and Royal Robbins, Harding's free-climbing rival, whose gecko-like prowess on the rock continues to inspire.

Both styles require skill and courage. But once again it's Muir who encapsulated the transforming essence of the experience, especially during his first ascent of Mount Ritter in 1872. Half-way up the crumbling mountain, Muir became gripped with fear.

"I was brought to a dead stop, with arms outspread, clinging close to the face of the rock, unable to move hand or foot either up or down," he wrote. "My doom appeared fixed. I must fall. . . . But the terrible eclipse lasted only a moment, when life burst forth again with preternatural clearness. I seemed suddenly to become possessed of a new sense. The other self -- the ghost of by-gone experiences, instinct, or Guardian Angel -- call it what you will -- came forward and assumed control. Then my trembling muscles became firm again, every rift and flaw was seen as through a microscope, and my limbs moved with a positiveness and precision with which I seemed to have nothing at all to do. Had I been borne aloft upon wings, my deliverance could not have been more complete."

It's those moments -- when you do something you think you can't possibly do -- that make climbing what it is.

Mr. Ybarra is the Journal's extreme sports correspondent.